The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has released the Kenya Comprehensive Refugee Programme 2016, which comes off the heels of the Kenyan government’s intention to close the largest refugee camp in the world at Dadaab.

The objective of the document is to lay out the priorities of UNHCR and partnering NGOs for implementing refugee programs. In all, UNHCR plans for a large number of returns in 2016 and 2017, but some of these numbers will be offset by new births at the camp (emphasis added):

“It is…anticipated that the decline of the Somali population will further continue due to the ongoing voluntary repatriation to Somalia, which seems to have picked up pace in the beginning of 2016, when over 2,000 refugees departed from Dadaab during the month of January alone (the equivalent of over a third of the entire number of returns in 2015).”

“As programming for voluntary repatriation gains more focus and support for returnees is enhanced on both sides of the border, there will likely be an increase in returns (UNHCR planning figure for returnees is 50,000 for 2016 and 75,000 for 2017). Based on this assumption, the total number of Somali refugees can decrease by some 25% (it is noted that the decrease will be partially offset by birth rate and new arrivals).”

So, UNHCR is planning for a 14.5% drop in Dadaab’s population in 2016 (from 344,648 to 294,648) and a 25% drop in 2017 (from 294,648 to 219648).

These are bold predictions because the number has not decreased annually by more than 10% in the last seven years, according to UNHCR’s own statistics.

UNHCR believes Somalia’s fragility — in combination with the potential for support at Dadaab to decline — could put refugees in an uncertain position in terms of whether returning to Somalia is desirable:

- Security, livelihood opportunities, and the populations’ ability to cope with shocks will improve slightly, but the risk of humanitarian crisis is likely to remain very high.

- A potential major regional drought late in the planning period (2018-19), combined with ongoing in security in Somalia, may influence population movements to Kenya

- If funding for Dadaab continues to decrease, it may cause a decline in assistance standards in the camps, which may trigger departures of Somali refugees

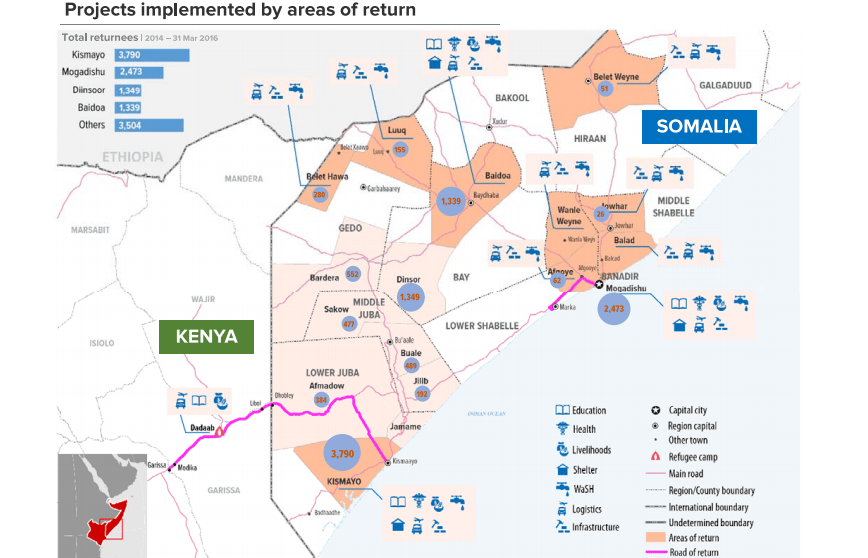

This month, the organization released a new map of refugee returns since 2014, and a few facts stood out:

- Kismayo district has the highest number of returnees in the country, followed by Mogadishu and perhaps surprisingly Diinsoor;

- Security along the main routes in Lower Jubba may be better than some assume if many returnees are able to traverse these roads (labelled in pink);

- Over 1,000 returnees have apparently returned to areas controlled by al-Shabaab, including Sakow, Buale, and Jilib. If these numbers are accurate, it will raise an ugly truth: sending refugees back to Somalia before al-Shabaab is driven out of its remaining strongholds may increase the number of people under the group’s control.

The 2016 programme also states UNHCR will advocate for Kenya to take the same approach as Tanzania in granting long-term refugees citizenship — or at least permanent legal status — for those who meet certain qualifications.

“…UNHCR will advocate with the Government for local integration of Somali refugees with strong links to Kenya and those whose status may warrant the grant of long term residence (e.g. permanent residence for spouses) and citizenship for children born of Kenyan parents.

The actual numbers will be determined through consultations with the Government. However, it is expected that some 40,000 Somali refugees or thereabouts may benefit from this type of solution during the next two years (2016- 2017).”

However, the Kenyan government is probably not as keen on mass naturalisation, and UNHCR recognizes it may be hard to get political buy-in for this idea:

“The Citizenship and Immigration Act offers opportunities for refugees to be registered as Kenyans on the basis of marriage to Kenyan nationals or lawful residence in Kenya over a prescribed period. In practical terms, it remains very challenging for a qualifying refugee to acquire Kenyan citizenship. Whereas there is no major interest on the part of most refugees to become Kenyans, the handful of individuals who applied in 2015 are still awaiting decisions on their applications.”

Nevertheless, some Kenyan members of parliament (MPs) agree with UNHCR and have made additional points about why Kenya should seriously consider naturalisation (via Standard):

“If you force these refugees to go back to Somalia where Al Shabaab is still active, they will be conscripted into the militant group and come back to attack us and they will come back to attack us,” said [Garissa MP Shukran] Gure.

The MPs argued that some of the refugees had intermarried with the local population and on that basis alone, they qualified to be Kenyan citizens. They said some of the refugees had Kenyan national identity cards. “Who will you be taking to Somalia, the wife, the children?” posed [Ndhiwa MP Agostinho] Neto.

Overall, how can Somalia and the international community prioritize the creation of sustainable opportunities for thousands of returning refugees and thousands of internally displaced persons (in Jubaland alone), as well as those already with more stable livelihoods in Somalia?

Academics, policymakers, and development professionals face a challenge in addressing this question in a harmonized and coherent way. But some helpful measures may include the following:

- More countries should offer refuge for Dadaab residents — especially if the international community expects Kenya to continue hosting the world’s largest refugee camp; in 2015, the main countries who accepted resettlement were the U.S. (3,610 individuals – 72%), Australia (514 – 10%), Sweden (341 – 7%), United Kingdom (308 – 6%) and Canada (174 – 3%), according to UNHCR;

- Kenya can develop a serious plan to naturalise refugees that meet certain criteria; in doing so, the Kenyan government would meet the international community halfway by introducing accountability measures of its own;

- Somalia’s regional leaders need to produce a framework for economic development in each region to complement a national development plan; Non-governmental organizations have useful data on different livelihood zones across the country that can be used for public policy planning; but regional leaders must get beyond basic tasks such as naming and re-naming regional officials and travelling abroad in order to focus on service delivery. The international community cannot financially support an economic transformation that meets Somalis’ aspirations without concrete ideas from Somali leaders.

Categories: Kenya

Kenyan Troops “Hid in the Grass” During Al-Shabaab’s Airstrip Attack at U.S. Base

Kenyan Troops “Hid in the Grass” During Al-Shabaab’s Airstrip Attack at U.S. Base  Weekend Note: Al-Shabaab and Kenya’s Tit-for-Tat Destruction of Telecom Infrastructure

Weekend Note: Al-Shabaab and Kenya’s Tit-for-Tat Destruction of Telecom Infrastructure  New Data: Main Factors Preventing Dadaab Refugee Return to Somalia

New Data: Main Factors Preventing Dadaab Refugee Return to Somalia  Around the Horn: Dadaab’s Decline, Kenyan Political Violence, and More

Around the Horn: Dadaab’s Decline, Kenyan Political Violence, and More

Leave a comment